The Cinegods Hive-Mind starts out on a communal tribute to Burt Reynolds and recovers some uncomfortable data that seems to be missing from the various remembrances blooming like toadstools all over the web… and YOU are THERE…

RAY GREENE SAYS: Okay, so the inevitable has happened. Burt Reynolds has passed. And the other inevitable has followed hard on its heels. Suddenly Burt’s a legend twinkling forever in the cinema firmament, instead of a cautionary, straight-to-video has been, which what he was by Hollywood consensus, oh, I dunno, yesterday?

Viola Davis–of all people–tweeted it best. “He WAS my childhood.” Mine too. From the moment I accidentally saw “Gator” (directed by and starring Burt Reynolds) at the drive-in as the second half of a double bill. The shot of 7 foot 3 actor William Engesser speed-driving a getaway car with his head sticking out of the sunroof still haunts my dreams.

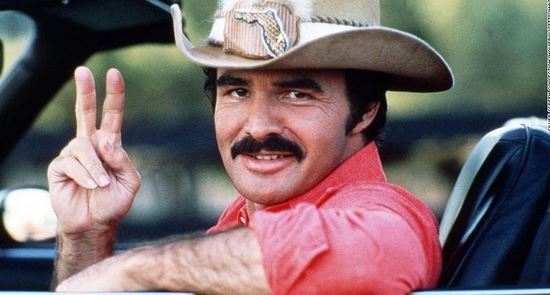

I could never get behind pretty much any of the Smokey-Hooper-Cannonball Run-Hal Needham artifacts, which are probably the iconic works in the same way that “Viva Las Vegas” has come to define the films of Elvis Presley. But I’ve always had a soft spot for Burt, whom I remember mostly in Polaroid snapshot form: the roguish talk show guest who set a gallant example in our ageist society by dating Dinah Shore, a woman 24 years his senior, during the “boy toy” phase of his career. The guy who struck another kind of offcenter blow for what he probably would have called “the ladies” as a centerfold for women in the pages of Cosmopolitan, and who thereby inspired a MAD Magazine parody musical called “My Fair Laddie,” which is how I heard all about it. And as the director and star of a movie that almost surely inspired Quentin Tarantino’s entire view askew approach to the crime drama–a sexy, exceptionally violent and altogether startling tongue-in-cheek update of Preminger’s “Laura” called “Sharkey’s Machine.”

“Sharkey” is one of the weirdest, most post-modern studio movies ever made, and based on it, I think Burt could have been a major filmmaker. He wasn’t, because he ended up loving superstardom, prescription pills and pitched battles with Loni Anderson more than he loved filmmaking. I think the fact that he was an athlete and stuntman may have had something to do with the prescription problems, and he was also severely injured on the set of his ill-fated Clint Eastwood team-up “City Heat” when a stuntman beat him over the head with a real piece of furniture in an otherwise routine fight scene, which he claimed was the start of his downfall.

“Sharkey” was a revelation to me as a kid (I caught it something like five times on HBO in its sub-run, which was like watching it on the bigscreen at my house because my dad was a sick cinephile and we had a PROJECTION TV). “Sharkey” was meta and self-reflexive in a time when the mainstream had no use for such arthouse nonsense, and it was breezy and funny too. I especially remember Bernie Casey’s death scene, which was played for laughs, in a tone I only encountered again when I saw “Repo Man” years later, plus the totally wack performance from Henry Silva as a coke snorting hit man–the only time this iconic B-movie actor has ever lived up to his cheekbones for me.

“Sharkey” is sly parody, and when you think about it, so was much of Burt’s performing career–his smirk was a constant reminder that he knew he was something other than an actor, which is why he probably ended up being such an unlikely influence on Jackie Chan. It isn’t surprising that Burt not only renounced his Oscar-nominated performance in “Boogie Nights”–he also allegedly fired his agents for setting him up with that career reviving role. That soulful performance showed he could operate as a character actor, but in the bijou of his mind, I think support was sucker billing.

He turned down the Jack Nicholson part in James L. Brooks’ “Terms of Endearment” to play “Stroker Ace” opposite Loni Anderson for Hal Needham, and by God, if he was anything like the Burt Reynolds of my imagining, I say he made the right choice.

WADE MAJOR SAYS: I couldn’t agree more with Viola Davis — Burt was my childhood as well. He was an undeniably transitional figure — for those of us too young to appreciate the allure of polished diamonds like Cary Grant, Gary Cooper and Gregory Peck; or rough-hewn, barrel-chested MEN like John Wayne, Robert Mitchum or William Holden, Burt Reynolds was something accessible — something forged in the tumultuous ‘60s and made for the free-wheeling ‘70s: a mischievous man-child who somehow managed to hone a persona that represented precisely what we needed, and when we needed it.

Burt’s movies were varied — but somehow he was always Burt. “Smokey and the Bandit” may end up being the part for which he is best and most fondly remembered, and it’s undoubtedly a seminal film: In a single swoop it resurrected Jackie Gleason’s career, elevated Sally Field from television to features, inaugurated a car chase genre that Burt and director Hal Needham would milk until it was bone dry (“Stroker Ace” and the “Cannonball Run” films), popularized the Pontiac Firebird Trans-Am to the point of societal saturation (at one point in high school, three of my friends drove Trans-Ams; and I once watched a Pay-Per-View boxing event on a street that hosted no fewer than twelve), and inspired a host of knock-offs, spin-offs and variations on the theme of the lovable muscle-car outlaw, the most memorable being television’s “The Dukes of Hazzard.”

My personal favorites, however, represent the extremes. In John Boorman’s landmark “Deliverance,” a film culled from our worst nightmares, Burt personified that vision of ourselves which our nightmares never allow — coolly and courageously pushing back against the walls of fate and inevitability. The usual escape from a nightmare is waking up — what makes them nightmares is that the dreamer is unable to prevail, unable to muster the courage or the fortitude to do what has to be done to end it all within the context of the dream. In “Deliverance,” Burt took control of the nightmare and incarnated a rare kind of movie anti-hero, poeticizing a kind of violence that might have been shocking in the hands of another director or star. Only the work of Clint Eastwood and Don Siegel from the same period can rightly compare.

On the other end of the scale comes “The End,” an underrated comedy classic that features Burt’s best work as both a comic actor and a director. Never properly given his due as a filmmaker, Burt Reynolds had an impeccable sense of timing and absurdism — his work with Dom DeLuise, though always enjoyable, rises to the level of Laurel & Hardy and Abbot & Costello in “The End.” That the subject of the film is suicide — the darkest of subjects wrestled into the lightest and most liberating of frolics — speaks volumes about his willingness to take risks at which any other star of the era would balk. It was — and remains — a bold, timeless and unbelievably hilarious movie.

Only a few months ago, I reviewed on radio his final film — Adam Rifkin’s “The Last Movie Star.” It didn’t even occur to me that this might truly be his last movie. Loosely based on Reynolds’ career, and featuring cleverly culled snippets from his earlier films, it felt like a tribute more than an obituary or an epitaph — after all, Burt had come back countless times before. On television with “Evening Shade” and in Paul Thomas Anderson’s stellar “Boogie Nights.” Burt Reynolds never really went away — he just transformed. The thought that he was eighty-two years of age also seemed a minor and almost trivial anecdote — ages were for other people. Not for immortals like Burt. I fully expected another comeback and more movies.

Now, however, he’s gone. For the first time in my life, there is no Burt Reynolds in the world. What he left us, is what we have. Burt has met his end and found his deliverance; and somewhere in that great beyond, Jackie Gleason and Dom DeLuise are as glad to have him back as we were to have him at all.

Rest well, Burt. You’ve earned it.

RAY GREENE: You’re right. He did take “risks” of sorts. Who remembers he played Barry Levinson (opposite Goldie Hawn as Valerie Curtin) in the movie made from their autobiographical screenplay “Best Friends”? Nobody. And even I had to look up the movie to remember its title.

Yeah, Burt had untapped potential. By the yard. That he didn’t give a shit about.

Which is why the cheeseaters will always love him.

He was them.

TIM COGSHELL: Love Burt and agree with all of that Ray. Especially the analysis of “Sharkey…”

But it must be noted – Burt hit girls. Judy Carne, Sally Field and Loni all say so.

Ah well.

RAY GREENE: I didn’t know that. And I was gonna call this “Redneck Messiah.” But I think we should hang a lantern on that kind of bs wherever we find it. ‘Cause it’s not okay, and deserves to be remembered.

So I think I’m gonna call this “Burt Hit Girls.”

WADE MAJOR: I never heard about his hitting anyone… so I would vote “no” on that. But the movies mattered. There’s plenty of time to revisit the man.

TIM COGSHELL: The naked pics and playing the boy toy, as Ray noted is what redeem him to me. Submission to the inclination of the women. He didn’t care what the guys thought about the older woman or getting naked for the enjoyment of women.

RAY GREENE: Well, having started this as a cockeyed tribute I’d like to take it somewhere else now. Because I just did the research. And Judy Carne and Loni Anderson definitely both said Burt Reynolds beat them. And if he did that, he was an asshole. Full stop. And I don’t want to celebrate his movies, any more than I want to celebrate Hitler’s paintings.

If people are going to make tributes to him AS A HUMAN than this totally belongs in the conversation to me. Because AS A HUMAN–and a well-muscled one at that in his prime–he violated other humans in a primal and I think an unforgivable way.

So I think the more fascinating question now becomes something entirely else. Which is: What does it say about us, as a society, that asshole woman beaters become our icons?

Steve McQueen? He beat his wives, or so they said. And thirty years on, Sheryl Crow wrote a song about how awesome he is.

Sean Connery? He beat at least one of his wives, according to the woman herself. And I believe her.

Was misogyny just so woven into the fabric of the times that it leaks out everywhere you look? Like pus from under an infected toenail?

I’m ashamed of myself for falling right into the trap that celebrity sets for us, by writing about this closeted asshole like I know him just because I liked a couple of his pictures and remember him in the margins of my childhood as some kind of mustachioed Sergio Aragones cartoon I could barely understand.

How about if I call this “Redneck Messiah aka Requiem for an Asshole”?

WADE MAJOR: Sally Field also said he’ll be forever in her heart. He wasn’t a saint. He was human. I’m sure he could be horrible. But a friend of mine, who wrote a script for him once, said, “He read a spec script of mine out of the blue 40 years ago and the result is that I have a career. So I’m grateful.”

I make a personal point never to celebrate who any of these people were privately because I don’t much like who many of them were privately, but also because I didn’t sign up to be anyone’s judge. I’m a critic and I can only evaluate their public work.

TIM COGSHELL: Sorry… didn’t mean to spoil the party…

I love Burt.

Yes… he was an old school ass from a generation of asses. We call him out for it. Check the box. Acknowledge. And press on.

He wasn’t a singular monster… he was an ordinary man, in this regard, but ordinary men from his generation were often wrong with respect to their views on women.

We say that. Indeed I just did.

Then there are the movies.

It’s no different that D.W. Griffith or Polanski.

They’ve gotta take it with them forever.

Post.