No Distributor. 2018. Comedy/Fantasy. 133 minutes.

Take a look at the below photo of Terry Gilliam on the set of his film The Man Who Killed Don Quixote. The director had been struggling to make a loose adaptation of Miguel de Cervantes’ 17th century novel since 1989 and this photo was taken around 2000, which is how long it took to get the project off the ground. It would be a short-lived victory: production was shut down eight days into shooting when French legend Jean Rochefort (left), as the knight-errant, suffered a double-herniated disc from sitting on that horse too long. Note Gilliam: lean, engaged, nary a grey hair on his head. A man in mid-career and in complete control.

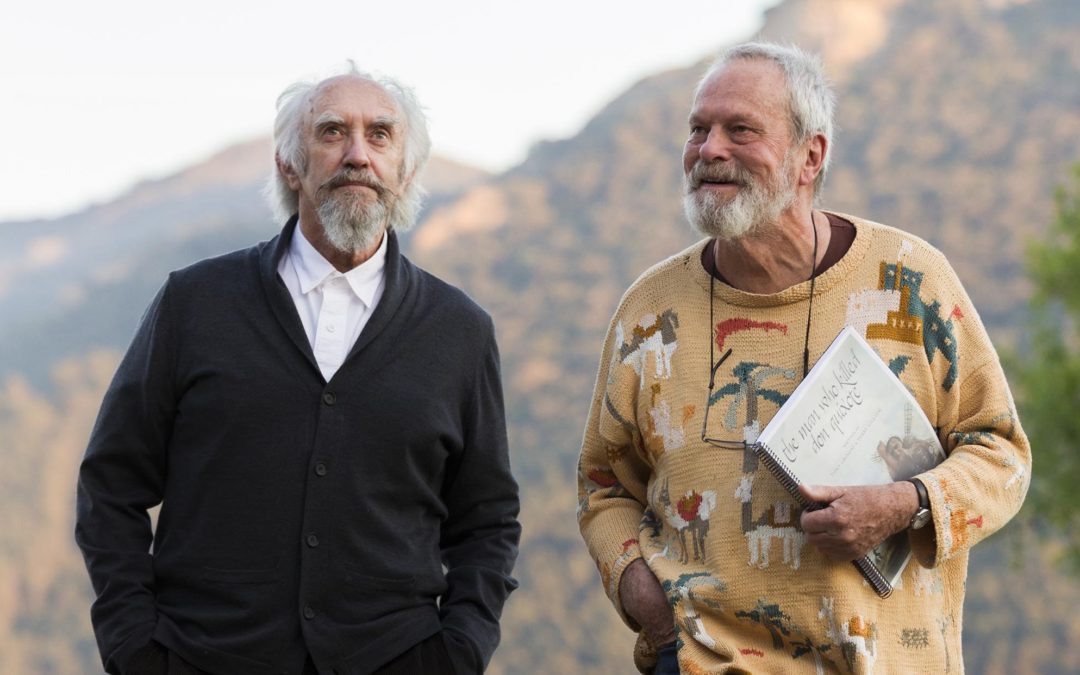

Now look at the below photo of director Terry Gilliam, also on the set of his film The Man Who Killed Don Quixote. This was taken after approximately 16 years of effort trying to restart what had become a legendary cursed production. This photo was taken around 2016. Note Gilliam (right): tired, looking slightly confused and completely grey, like he’s about to ask co-star Joana Ribeiro what year we’re in or, possibly, the location of the nearest bench.

This is what happens when you spend almost 30 years trying to make a movie.

Indeed, the protracted birth of “The Man Who Killed Don Quixote” extracted more than its pound of flesh from Gilliam as it hopscotched between banks, boardrooms, cutting rooms, screening rooms, courtrooms and, occasionally, a shooting location. For a full accounting of Gilliam’s agony, watch Keith Fulton and Louis Pepe’s warts-and-all “unmaking of” documentary “Lost in La Mancha”. It’s a terrific chronicle of one man’s perseverance, frustration, bad luck and heartbreak. When it was released, in 2002, it would still take another 16 years to complete the film.

But for those who think Gilliam’s delivery of his long-awaited final cut is the happy ending to a Michener-length story, you haven’t been paying attention. In April 2018, the movie’s Portuguese producer, Paulo Branco, sought an injunction to prevent “The Man Who Killed Don Quixote” from premiering at the Cannes Film Festival. The motion was denied by a Paris judge and the movie unspooled to mixed reaction. According to Gilliam, in 2016 Branco contractually agreed to fund the movie and when he didn’t, the production found funding elsewhere. Branco sued for breach of contract claiming his deal with Gilliam awarded him rights to the completed film and last month a French court agreed and ordered Gilliam to pay Branco $11,600 in damages. The film has since been released in France and a few other territories. However, Amazon Studios, its original American distributor, pulled out, partially after getting spooked when Roy Price, the Amazon exec who approved the deal, was fired last fall in a sexual harassment scandal. Presumably no U.S. distributor will touch Gilliam’s movie until it’s cleared of its legal liabilities, and that’s assuming said distributor foresees any commercial potential.

But that potential, alas, is represented by a precious few moviegoing groups, including Gilliam completists, inquiring minds and anyone seeking refuge in a large, empty room. Even they may not be surprised that the film is such a demoralizing misfire. What might have been a career-encompassing statement from the 77-year-old Gilliam about his approach to life and moviemaking is, instead, the tired, compromised and rather cheap-looking work of a director once compelled to declare that he wants “to get this film out of my life so that I can get on with the rest of my life.”

So you’ll excuse Gilliam for the opening title card that reads, “And now… after more than 25 years in the making… and unmaking.” Cheeky, to be sure, especially in opening credits that also include the words, “tax shelter”, which hardly augurs an evening of auterist cinema.

And Gilliam is, by any definition, a genre unto himself, a name brand director who has spent much of his career promoting the notion that imagination is more vital, life-affirming and, often, preferable, to reality. Sam Lowry, Baron Munchausen, Parry and Don Quixote all escape into their own heads to become better versions of their earthly selves. But whereas “Brazil,” “The Adventures of Baron Munchausen” and “The Fisher King” maintain an internal logic and narrative coherence that guarantee Gilliam’s oft-articulated concerns never disappear beneath his Monty Python-honed visuals, “The Man Who Killed Don Quixote” is distracted and unfocused. It’s something the director himself might have even sensed. Late in the game, during a surreal, Gilliam-esque costume party in a Spanish castle that comes long after the film has spiraled into the ground, disillusioned commercial director Toby (Adam Driver) is told, “try to keep up with the plot.”

And what a plot it is, a confused and mangled thing with fuzzy character motivations, two go-nowhere love interests, left field exchanges about Spain’s religious history and a confounding scene where Toby sings Eddie Cantor’s 1920’s chestnut “If You Knew Susie” in front of a confused Don Quixote and at least one crestfallen audience member. If it took almost 30 years to refine the script to this point, imagine what it was like in 1989.

Actually, we know what its earliest iterations were like, back when it was threatening to be one of the most expensive films ever shot using European money. Toby (at one point played by Johnny Depp) was to travel back in time to the 17th century and become Quixote’s sidekick, Sancho Panza. In the cheaper, 2018 version, present-day Toby is in Spain directing a Quixote-themed vodka commercial. At a restaurant, he happens upon a DVD copy of the student film adaptation of “Don Quixote” he directed ten years earlier in the nearby village of Los Sueños, (Spanish for “dreams”) starring elderly local shoemaker, Javier (Jonathan Pryce). Toby sets off on motorcycle to find the village and discovers that Javier has spent the subsequent decade believing he really is Don Quixote. Gazing upon Toby, he believes his long-ago director is Sancho Panza.

The set-up promises to address a bounty of issues about personal responsibility, the corrupting influence of money, the desire of ordinary people to transcend their ordinary lives and art vs. commerce. He mostly shelves these ideas as Quixote sweeps Toby up in a hurricane of fantasy and reality-blending incidents across the Spanish desert. For reasons not hard to fathom, the one theme that resonates most is the corrupting influence of the movie business. Returning to Los Sueños, the arrogant Toby learns that the local who played Sancho is dead and 15-year old Angelica (Ribeiro), who played Quixote’s beloved Dulcinea, left Los Sueños for an acting career and became, in the words of her bitter, innkeeper father, “a whore.”

As for Quixote, he’s survived as a literary character for over 400 years partially because he’s so malleable as a social, moral or political symbol. Gilliam signals his intentions early on when Javier, in full Quixote regalia, gets comically tangled in a tattered, makeshift movie screen. It reminds us that Gilliam’s off-screen and on-screen obsessions often merge and that his best films feature characters who cannot, or maybe choose not to, distinguish between fantasy and reality. That’s why it’s all the more depressing as we transition from thinking Cervantes’ novel is the perfect match of director and material to wondering why Gilliam was interested in adapting the book in the first place.

Driver’s odd and gangly looks have made him one of the most fascinating leading men of his generation. His large facial features and marionette-like physicality combine with an acting style and on-camera presence both rugged and natural to create something truly special. He is unique in the best possible way, so watching him perform as if he knows he’s in a Terry Gilliam film can be irksome. Possibly taking his responsibility as audience surrogate a little too far, he drops panicky, disbelieving F-bombs at regular intervals. Instead of bringing us closer to the character, they bring us closer to the actor, as one imagines Driver thinking the same thing we are: Is Toby’s purpose in this story to make amends for what his student film wrought upon the poor townsfolk? Is Quixote the spark that motivates Toby to trade ego and sin for the liberating power of imagination? Is he the Gilliam surrogate or is Quixote? If Driver would calm down for a second, I’d love to ask him. Pryce is always wonderful and is mostly wonderful here, although, presumably for lack of any arc to play, he becomes broader and broader until one scene where he starts hopping around making animal noises to which Toby, if memory serves, responds by dropping another F-bomb.

Elsewhere, the reliable Stellan Skarsgård, as Toby’s scowling, money-first boss (credited as The Boss), mostly skulks around and reminds Toby that he “must land that account!” while Alexi (Jordi Mollà), the Russian oligarch who bankrolls the climatic Holy Week party that affords the movie its one chance to go full-Gilliam, helps cement the film’s tone-deaf treatment of women. Angelica is a former escort girl so demeaned by Alexi she’s forced to lick his boots, the Boss’s wife (Olga Kurylenko) is a philandering sex hound and one crew member is so anonymous that Toby can never remember her name. While surely Gilliam wanted this thing released before God Knows What happened to it, today’s course-correcting social climate would make 2018 the least advisable year to put these female characters in front of the American moviegoing public.

The perseverance Gilliam demonstrated by seeing this torturous project to its completion does not generate enough goodwill to make us forget that the film is a soulless chore. Whatever personal statement Gilliam wanted to make in 1989 is certainly not the statement he has made three decades later with the completed film. Just like his most memorable characters achieve their greatest potential in their own imagination, the best version of this material, and the best explanation of what the story means to him, remains in Terry Gilliam’s head.